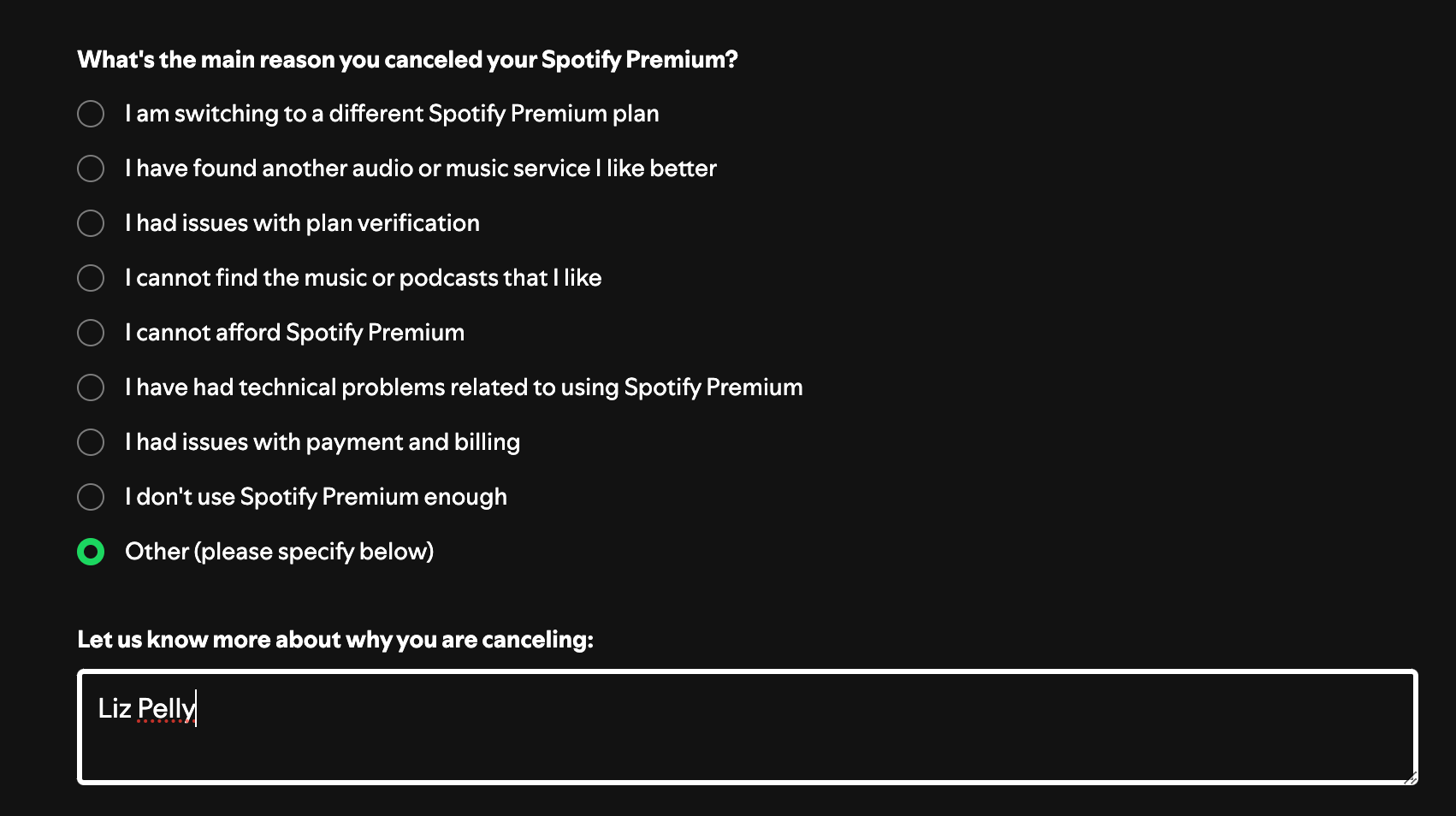

Why I quit Spotify after a decade

- Mood Machine by Liz Pelly. Published Jan 2025. Read Jan 2025.

Spotify is bad for artists and bad for listeners. I didn't always think this, but I do now. Or I should say, I didn't always know this. You can't think the thoughts without knowing the knowledge.

The knowledge is provided from Liz Pelly's first book Mood Machine: Rise of Spotify and the costs of the perfect playlist. In it, she asks us to question a titan. Question the billion dollar super streamer app Spotify, which seems to be unstoppable: 30% of the market, over 600 million users, and over 260 million paying subscribers. They just made their first profit. (15 years after being founded).

Pelly, a writer and editor and who has been writing about Spotify for nearly a decade, is ready to take it on: “I’ve long been confounded by the expectation that we simply accept the dealings of the powerful as unexplainable,” she writes in the introduction.

I'll admit, I was one of those people who accepted Spotify's deal with major labels, its way to growth and popularity as unexplainable. I accepted that it is a good thing it costs me like $10 bucks a month for unlimited access to most of recorded music. "It's impossible to quit," I've heard friends say — what I've said — about posing such a modernly radical idea: would you quit Spotify?

For nearly 15 years Spotify has played middle man to my relationship to music. It's been the same neon green room I've "sat" in year after year. I started as a CDs guy: stacks of plastic cases stacked in my bedroom next to headphones; car sleeves and constant zippers to swap out albums and mixed CDs; the platinum color of blank CDs scrawled with Sharpie, which were full of songs ripped from a friend's much-faster-than-mine internet. I went to record stores too, putting on headphones to preview new albums, smell the incense, clack through crates and stacks, see people with tattoos and ripped t-shirts. I knew the clerks. It felt like a portal, the slow and steady look for albums, the frighting guess of deciding to purchase an album without knowing if I'd like it.

Later, I had an old iPod bought used off eBay, and in a rush to spend some saved cash in a tin can on the side of my bedroom from a golf course gig, I bought a brand new Zune. I got Microsoft's digital music device to be "counterintuitive" and different; everyone had an iPod.

I took the Zune to college and plugged into a boombox that I lugged it to each new home I moved to across four years. My music went digital. But I also frequently went to shows, stood in crowds, drank cheap beer, met other fans, bought more CDs and felt the collective rush of live shows. I hit up after parties, chat with bands, take in second-hand smoke, smell sweat and hot palms. My body felt like a tuning fork the next day; even if I was tired (hungover). My heart and head still felt like it was in a jacuzzi for a few hours — some zone of dance and possibility. I was buzzed with social connection, experience. I should have done more of it.

When I moved to NYC in 2015 and got my first smartphone I turned to Spotify. I stopped buying music. I stopped looking for music. Stopped going to independent record stores. More each year, I went to less and less shows. I offloaded this all to Spotify. I sat on trains and loaded the app, downloaded podcasts and songs. Music lost its worth. Music lost it's source. It was something delivered on playlists, Velcroed to moods.

Pelly comes to this work knowing the DYI and independent music universe — a kind of anti-corporation world of collectiveness: a debated definition that generally means artists split any profits or royalties with a major label fairly, 50-50. This isn't the case with streaming now, or with major labels.

Independent music also means a whole world of alternative networks outside mainstream/major labels: independent distributors, record shops, zines, blogs, radio stations, and venues. All of this contributes to music culture. And all of it has been threatened by Big Stream.

Independent music promotes the idea that music is social — it has context. Big Stream makes music more anit-social: its goal is to be an app where you push one button and never have to think about what music you want again.

Spotify shepherded the "legalization" of pirated music while also broadcasting accessibility for fans and artists, and fanning the fires of hope labor to artists: you give enough of your work for free, and make it a certain way, you'll be picked and make it on the platform. In doing so, it forced independent artists into a mainstream economy of how music gets made, distributed, bought, and listened to. As Pelly writes:

...the very concept of music streaming was designed for the benefit of extremely popular, major label music. But independent musicians have also been expected to conform to its one-size-fits-all model. This is strange and new: independent music has historically maintained its own economies, with its own retail outlets and promotional ecosystem, with dedicated fanbases particularly likely to pay for records and downloads. And while it has become common rhetoric to discuss the algorithm-driven platform era in terms of its flattening of aesthetics, this is also part of the flattening that has occurred: the flattening of the winner-take-all pop star world and the working artists of the independent world. Flattening might really just be another way of thinking about media consolidation.

Even though I've probably listened to more music in the last ten years than I ever have, I've probably never known less about the musicians and music beaming from my phone. I don't save or revisit many albums or artists, and have been way less likely to re-listen to something. I've been taken out of the culture of music.

Pelly writes for The Guardian, The Baffler, NPR, and other outlets, where she has reported on Spotify over the years. Pelly has done the work: traveled to Sweden to see where the company was first founded, talked with artists, been to shows, chatted with former Spotify employees, seen internal Slack chats and documents, read widely, and so much more.

Each chapter in this book is a blue flame creating a burning tundra of an evidence for why Spotify isn't good for artists and listeners alike. She maps for us for how we got here, and what we might be able to get out.

For artists, it forces every musician into a pop star economy. Every musician, rapper, artist, singer, bandmate, producer is thrust into song engineering for mass scale and popularity. Artists only get paid livable wages (artists get paid less than a cent a a stream) if their song becomes popular.

To become popular, you need to make songs a certain way. Lance Allen, a guitarist Pelly focuses in one chapter, was such an artist. Allen worked hard and got on the "Peaceful Guitar" and "Acoustic Concentration" playlists: he started paying for his mortgage, bought a new car. He was living off of his Spotify checks. This was marketed as Allen's grit, determination, and playlist pitching that brought him success.

But in 2023 stock music had replaced him. For Spotify, it was cheaper to use stock music, and for the listener just wanting guitar music in the background, it didn't seemingly make much of a difference. Music made by mysterious studios and production companies Firefly Entertainment and Endemic Sound had pushed Allen off the playlist.

Allen didn't make the same kind of money as he once did, or make the same type of living. Spotify incentivies artists and musicians to create mass-scale music when historically many artists don't have this aim. Rather than scale, they want to sustain — enough to make a living, buy health care, be a part of a culture.

This flys in the face of Spotify's mission:

Our mission is to unlock the potential of human creativity—by giving a million creative artists the opportunity to live off their art and billions of fans the opportunity to enjoy and be inspired by it.

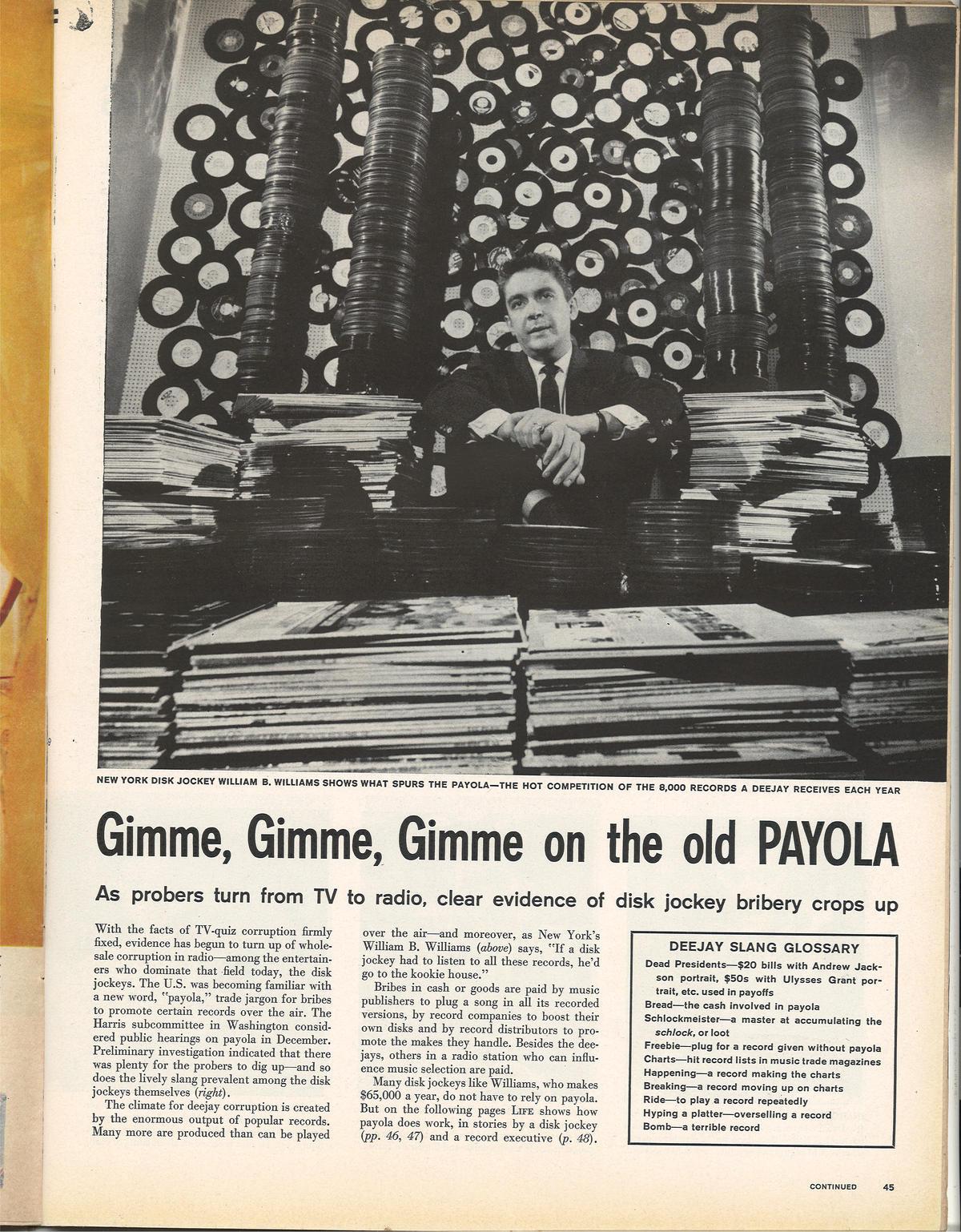

To become more popular, some artists even take pay cuts on royalty checks to be featured on Discovery Mode, echoing an updated version of the 1950s payola scheme.

Like other platforms, Spotify becomes the boss. You do what makes you popular on the platform. I've noticed this on another platform, Linkedin: certain posts and ways of writing and types of content get rewarded. There's a whole cottage industry of people posting about how to post on Linkedin. The platform also doesn't often reward web links of any kind (this is why people put links to other webpages in the comments).

To keep my Linkedin tangent going: To me, support for web links is the basic requirement of the web, as blogger Dave Winer has written. "In the same way we say feeds are required to be a podcast. If you don't support links not only aren't you the web, you're anti-web."

Having diverse options of sources is kind of a basic requirement for music. Instead, for an artist on Spotify, the platform tells you what kind of music to make, rather than the artist telling the platform what they are going to make. This flattens creativity.

So rather than being themselves, everyone is gaming to be popular. Unless a Ghost Artist who is paid to make "lean-back" stock photo-versions of music, fills the void, which Pelly also writes about. Or soon, as I can imagine, AI-generated stock slop will take the place of people all together.

https://harpers.org/archive/2025/01/the-ghosts-in-the-machine-liz-pelly-spotify-musicians/

AI-generated music is something co-founder and CEO Daniel Ek has shown enthusiasm for in past reporting, too.

As Pelly hears from those in the industry: what does this all mean? What kind of music isn't being created because of this?

Listeners miss out on a diversity of music, and artists stop making non-popular music. Listeners are siloed to their playlists, and only hear what Spotify boosts or shows. In addition to being cut off, when you type in an artist, or build a playlist of your own, the app collects data on you. In turn, that data determines what music the app shows you, or what music will get boosted in the broader ecosystem.

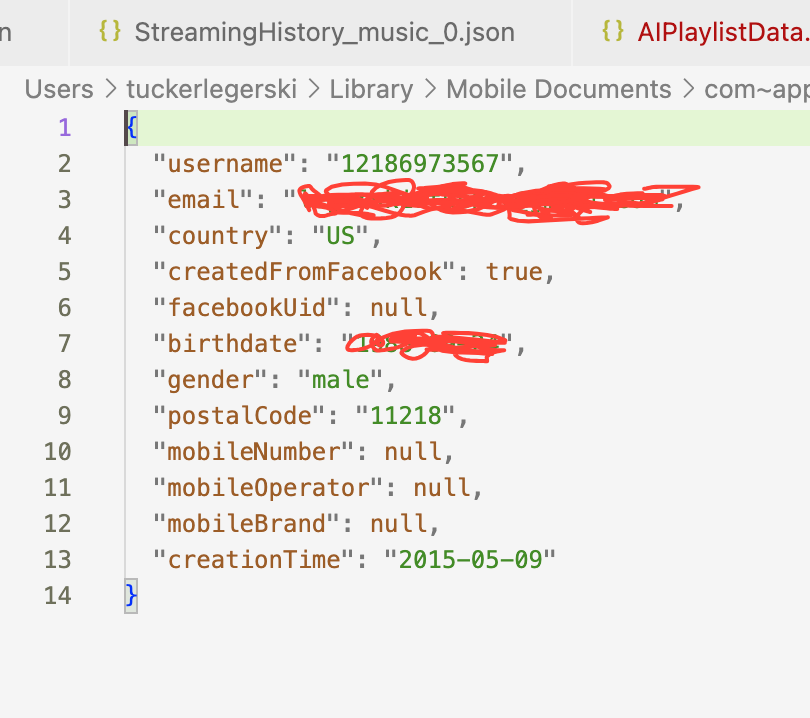

You're never alone when you use Spotify. The data grabbers of Spotify are there collecting everything your thumbs touch in the app. They are there to sell you ads, sell you to advertisers, to figure out what music is most popular, and makes the most money for Spotify. Users are numbers before they are music fans.

Discovery, friction are downgraded by design. It keeps you siloed and anti-social with an art form that has always, dating way back like when people drummed around a fire, been about being social. But, as Pelly explains, it is hard to create conditions where people can organize and collaborate:

It is hard work—the polar opposite of the frictionlessness that platform-optimized tech culture imposes. But friction is part of how real connections, and ultimately change, happen.

The pages of Mood Machine operate on the robust economy and collection of its information. Like all stands against titans, it reveals a new narrative — it knocks away a mind control. Spotify, for me controlled my relationship with music.

I would put Pelly's book on a shelf next to Rob Copeland's investigation into Ray Dalio or Lila Shapiro's into Neil Gaiman, or the works of David Gareber like Bullshit Jobs. The evidence from reporting and longtime experience flips an assumption on its head: these people and companies aren't what you think they are; the popular narrative is wrong.

Pelly was partly inspired to write her book because she stumbled into writer and activist Astra Tayler's The People's Platform, which argues that the idea of the internet providing more equality has become a lie the public is given.

The Platforms, the internet power houses, often sell an idea — good for creatives! Democracy! Everyone can become rich! — when really they are more often turning you into the product for ads, and, in the process, reinforcing inequality.

https://us.macmillan.com/books/9781250062598/thepeoplesplatform/

Spotify was actually founded as an advertising firm — music was just a way to deliver ads. The files were easier to use because the file sizes were smaller than video. It wasn't about the love of music, or the love of improving the economy of the music industry, which well before the internet, had problems. Spotify has just evolved those problems, not fixed them.

There is plenty of other bad stuff about Spotify that you can find in the book, but a top reason for me is the mind control. It stops you from thinking. It devalues music, makes it seem like it costs nothing for people to make. The imagination, creative labor, recording work to put something together loses its value because of the endless options. Music also loses its value in my own personal culture in how I spend my time and what music means to me.

Spotify erases the labor and effort to make music a reality. Spotify makes it feel like support for an artist lies in us, the consumer and fan, rather than the systems and industry. If music is just content for ads, or bigger draws for subscribers, then it's more about making that content — that music — as cheaply available as possible.

But does this mean we should all go back to the days of CDs and buy every song and album we want to listen to? What if we can't afford that? It's not necessarily what Pelly wants: "Something that can be complicated or seem like a contradiction in some ways is that I actually am in favor of universal access to music," she told the hosts of the "Hard Fork" podcast.

"I don’t think universal access to music is a bad thing. And I’m someone who came up in the era of Napster and file sharing. And being able to access a lot of music that way was really influential and formative for me, I should say."

More access to music (not paying for everything you use), to arts in generally, is good. It's why libraries are good. I'd argue that this book advocates for better protection of the labor that goes into making culture, more broadly. This means Big Stream should pay artists more, care about them more — even the ones who aren't streamed millions of times. Major labels should pay artists more too while also providing human infrastructure like healthcare.

More streaming services and business models should be created, libraries should offer more streaming services and local programs for local musicians; policies should emerge to give artists an easier way to make a living and survive. There is no one-size-fits all to fix the challenges that Big Stream has created, but they are there. The solutions are more about power structures than any choice a listener makes.

For Pelly, beyond valuing musicians, the more important thing for listeners to pay attention to is how Big Stream takes away people's ability to think. The mind control part of it:

For me, it’s the rise of and championing of lean-back listening, of a sense of passivity, of this devaluing of music, not just on a financial level, but in some ways, on a more cultural level that I think happens when this relationship with music is watered down in this way. And of course, Spotify didn’t, and streaming didn’t create these conditions, didn’t create the idea of the lean-back listener, for example.

But I think that this way of music has been really exacerbated by streaming, by making lean-back listening the most frictionless way to engage in music. I think that optimization and frictionlessness has been really disastrous for culture, beyond even music. I’m a music critic also, and a cultural critic. And I think that thinking is really important. And I think that encouraging people to think is really important.

https://www.nytimes.com/2025/02/07/podcasts/hardfork-doge-spotify-tools.html?

Thinking is anti-Spotify. Thinking about the something created (what platforms call content) is the antithesis of many platforms, including Spotify. Pelly has written a book that, to me, signals a possible counter culture: counter to siloed platforms, counter to off-loading thinking, cultural taste, and discovery of information to a giant corporation.

This book is also a welcomed pillar for a larger argument against the corporate culture capture that so many of us have lived with for nearly 20 years. Like how Netflix has snagged films & TV; Meta sucked up social time and the news; Amazon caged audio and ebooks; the BigAI companies have snapped up much of the written word and images posted on the internet. All exploit creative labor and extract user data to some degree.

Pelly builds out hope for this counter world where people come can come together, humans reject algorithms, friction and celebration of cultural creation can occur. She might make you think about it; at least a little bit.

After a month of thinking about music again, I can say it's different. I've listened to more albums in the last month than I have in like three years. I have kind of dabbled in Apple Music, who pay artists more, but the problems still exist there, too, as Pelly points out near the end of her book. So I'm limiting my time in that.

I do also stream music on the indie marketplace and info center Bandcamp; check out live shows on YouTube; I listen to indie radio, read newsletters, buy a few records and CDs. I am starting to talk to people about music again, too, and seeking other ways I could make it a part of my social life. But by thinking about music, it feels more human. I feel more, yes, connected. I'm even having more fun with listening to music. Rebuilding this part of my life and taste will take time, but at least this is a start.

If you're interested, read Liz's book, and she'll tell you all about it. Or you can check out these other resources, too:

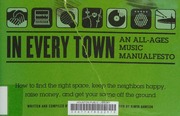

Check out In Every town: an all age "manuelfesto" on DYI music scenes across America (a bit dated...we need a new one of these!)

Advocate for better policies and support musicians labor organizations:

Advocate for better policies around technology that seeks to serve people rather than exploit them.

Advocate for forms of universal incomes and artist programs like in France or Ireland.

Buy music; buy from independent labels, Bandcamp, or from record stores. Buy music in general and build your library! Digital, records, CDs, anything.

Go to shows! Go to local events! Meet people.

Text a friend a suggestion, or ask a friend for a recommendation.Write about music and post it. Make a video, a podcast about it. On a recent interview, Pelly considered both of these as social. It's forcing you to engage deeper and creates a bit of that friction, where true connection happens.

Join a music group, learn an instrument.

Listen to interviews from artists — hear what they recommend or are listening to.

Listen to the podcast NPR's All Songs Considered:

https://www.npr.org/sections/allsongs/

Read Hearing Things website:

Listen to indie radio and internet services (with human DJs). See NTS, 88Nine music; the Current; KEXP in the Bay Area; Eclectic 24...many of these are on Apple Music to stream, or have their own apps.

Member discussion