What The Pitt reflects

"Keep your eyes on the waiting room. Make sure no one is going to die out there," the weathered, wise, and emotionally sharp Dr. Robby tells a group of med-student/in-training doctors on The Pitt, which I started watching last night. The room is stuffed, every chair full, people standing.

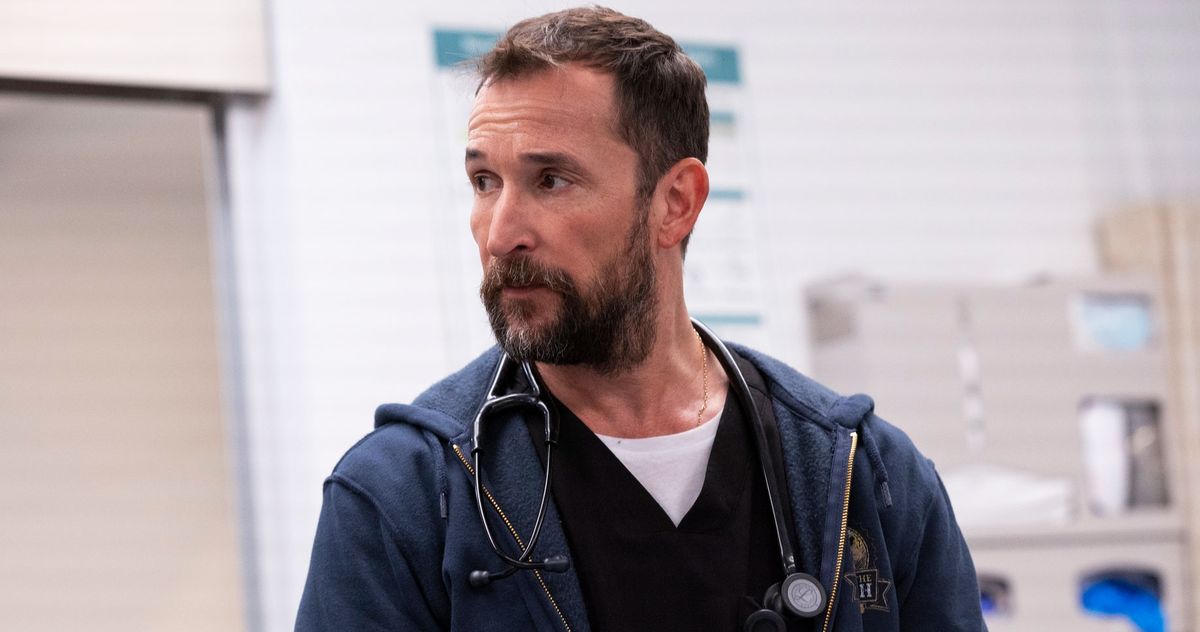

I craved air seeing this waiting room. Hair unkempt, people vomiting, chest pain, shuffling, pain filled bodies against the wall, on the floor. A tired, broken citizenship waiting for care. All waiting in the grind of hours-long wait. It's a scene — the dreadful waiting room of a fictional Pittsburg hospital. Dr. Robby is Michael Robinavitch (played by Noah Wyle, who is back in scrubs) who is our tour guide into the pit.

I'm hooked on The Pitt. I've never worked in an ER department, but I've been in one plenty of times. And I spent 3 years working in children's hospitals. It felt accurate. Plus, the stories sizzle. You get a wide range of mini dramas inside of the ER: sickle cell, nail to the heart, first-day-on-the job med student; pregnancy; mean-spirited cynic who is good at medicine; dropped off gun shot victim; teens overdosing on fentanyl; rats let loose from a patient's jacket; hot breath admin demanding to get patient satisfaction up; a charge nurse who is too nosy and asks too often if her fellow staff members need personal help. This is just a few of the stories in the first 3 hours (Pitt goes 24 style with every episode representing an hour of a day/shift, but unlike Jack Bauer, these characters actually need the bathroom; actually take a smoke break; actually feel breakable).

The Pitt is an appropriate title. It's a crowded soup of stories inside an ER, inside a a section of the hospital that can feel like a living pit of monitor, scrubs, IV bags, beds, curtains, and hurting bodies. Patients and staff bunched together — the camera swings from room to room as it all feels like a long shot. We scamper a few feet into a new life and situation, swinging back and forth between the staff and their patients. We follow a squirt of hand sanitizer, a doctor staring at a computer monitor; a med student with a surgeon mom who works up stairs; a scrub change from spilling medicine; a runner passing out suddenly in a hospital bed; a regular to the ER talking inappropriately from her wheelchair; worried parents looking at their child with a tube down their throat; an injured patient who can't speak English and needs a translator.

Every inch and minute has a new drama built in — stuck in the circular, windowless space that's a mess, and a breathless whirlwind of shifting rotations. It's hard to believe this much can happen in an hour, but even if it doesn't, I am willing to suspend beleif: the characters and stakes, and the novelty in each episode so far, make it compelling to watch. One way or another, most every patient fell into being there (maybe the doctors and nurses, too). They didn't desire to be stuck in this place. They were living their life until suddenly, something happened: from gun shot to vomiting to headaches. The something can happen slowly or quickly. Suddenly you're down in a place you didn't expect. It's a pit. Everyone is just trying to figure out how to survive it; how to crawl out. Even if you're forever changed because of being there.

The characters bubble, the pacing feels a bit whiplashed (this is TV after all), but it's entertaining. Grounded drama in the backdrop of a hellscape medical system. Dr Robbie is the wise teacher, the heart the size of a continent, experience mysterious as moon craters, but useful. Everyone is there because the want to help the needy. The show champions the thankless work happening in hospitals across America.

These jobs are what Fobazi Ettarh would call "vocational awe." Ettarh wrote about librarians, but I'd like to extend it to the medical profession. These jobs are jobs people do against their own self interest — they feel the must sacrifice, struggle, be obedient. It's supposed to suck, but because it's a passion, or a drive of good will, all the struggle is okay. They do it because they feel it is right. But you can't eat on passion, or pay rent on it, or mentally sustain on such professions. In some ways, The Pitt is a siren for the those unfamiliar with the setting, for those who may have forgotten the horrors of the pandemic. It's a reminder our systems should care for these people: better support, less debt, better organization into labor solidarity (h/t to Cory Doctorow). Those who serve in any capacity deserve to be served, too.

Another touchpoint for The Pitt is it's being praised by real-world doctors. Doctors and nurses are seeing themselves in the show. Partly because the doctors don't feel like glossed out movie stars wearing scrubs and stethoscopes. Doctors, nurses are seeing themselves on screen. The writers have ER experience, experience writing medical dramas (like the drama, Wyle's old claim to fame, ER.) They also brought on plenty of consultants who helped bring reality to the dialogue, the atmosphere; every inch feels like the place. Here is a show we need, now. A show that feels real enough to reflect the difficulty and grace of a vocation often forgotten. Doctors, nurses, hospital staff are there with teachers, artists, librarians. They are the people we need.

In an interview, Gemmill and Wells said the aim was to create as authentic a portrayal as possible. Recent changes to the real-world culture surrounding medicine — the decline of primary care, the enduring trauma of the pandemic, the creeping privatization of hospitals — lent themselves to a different, more grounded conception of drama. And the fact that the show is on Max, which permits a degree of graphic language and imagery that is not possible on a broadcast network, encouraged a more gloves-off approach to the writing.

In Ny Times by Reggie Ugwu

Member discussion