The $35 billion market you don't know about

In recent years, a global and booming cross-border human egg economy has taken root. Couples and individuals receive and use donated eggs from countries across the globe including India, Greece, Argentina, Taiwan, China, Australia. The US often serves as a the zone of treatment and deal exchange. As one traveler to the US put it: he values America for its "transparent capitalism.”

It's a webbed network with thousands of dollars at stake for individuals, clinics, and agencies — all with very little oversight or tracking of eggs.

An excellently reported piece in Business Week chronicles this trade and how couples tap "into a growing global industry that caters to struggling couples from parts of the world where egg donation is heavily restricted or cost-prohibitive."

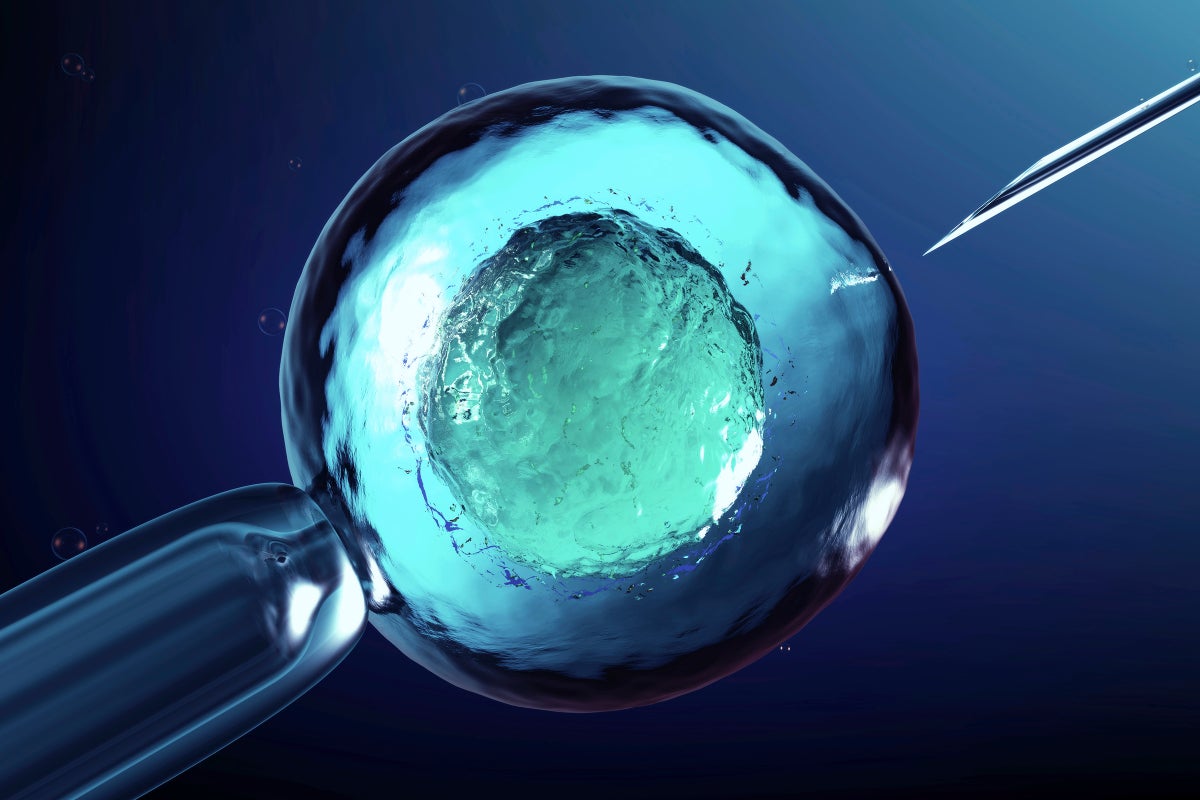

Most IVF treatments involve women using their own eggs. In at least 6% of cases the eggs come from donors—the fertility industry’s term—who agree to have their eggs removed, often in exchange for money. The donors are recruited into a $35 billion-and-growing global market for assisted reproduction. This market comprises would-be parents, agents, doctors and clinics—many of the latter backed by Wall Street and private equity.

Women are paid thousands of dollars for their eggs by organizations like Growing Generations. For some, like poor and low-caste individuals in India, it's hundreds of dollars, but life changing money. For some in Taiwan, or Argentina, it's a sizable side gig that enables lifestyle change with hundreds of thousands of dollars funneling into donors' bank accounts.

Having children becomes a way to make money, exploiting some, enriching others, and genuinely changing the life of couples. This network trade seems to affect both the wealthy and the poor.

If you're buying global fertility services, you often pick the genes you want based on photos and in-depth profiles. It can seem strange, and drift into a version of eugenics.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/1467-8519.00251

I, a hope-to-be parent using IVF, admittedly participated in choosing the best viable embryo, but not with donated eggs. The supply came from us, the two would-be parents. We tested for a few genetic anomalies — then it was about picking which embryo will most likely make a fetus, and then a human baby. We didn't need more data beyond that.

If you have lots of money though, expensive fertility outfits backed by VC money offer a further step of screening genetics with polygenic risk scores — often relying on Eurocentric data sets — to try and predict what genes might cause illness and disease. A company like Orchid wants to screen for intellectual ability, skeletal defects, breast cancer, prostate cancer, type-1 and 2 diabetes, and many more. If your embryo had a high chance of having one of these, would you move forward, or choose another embryo? Would you do the test in the first place?

If my own crooked bones had showed up on such a test (if it existed), and my parents didn't want a kid with crooked bones, I might not have existed. The same could be said for my mother, who had type-1 diabetes. What does it mean to pass on an embryo who might have these traits? Are these traits truly the enemy?

There is no guarantee such testing totally predicts these genetic outcomes — but it's another area dominated by data and metrics. Data is wielded to control. Data is used to stop all chaos — challenging and beautiful alike.

Every would-be parent wants the best life for their child, but how do we know what traits lead to the best life? Are "flaw"-free genetics a guarantee for the best life? In my opinion, stamping out diversity in desire of culturally/societal manicured as "good" genes is a dangerous game to play; especially if the wealthy are doing the picking of those genes.

Genetic engineering, on any level, can lead to the elimination of "undesirable" genes. This is a form of ableism, racism, and sexism. We should not use technology to eliminate human diversity. We should create infrastructure and resources for all types of bodies, celebrate them — rather than try to shun and hide them from public, or from imagination. As a future parent, I want the best conditions for my child. But I also want to embrace and accept who they become — flaws and all — no matter what "crookedness" they may develop. Crookedness in body, mind, or soul isn't a bug — it's a feature.

Tech enables possibility, science makes magic happen: a birth — a whole being — when it was not possible before. As couples turn to this global and billion dollar market, I hope we can understand the power in the tech. In the Business Week piece, a rare relationship between donor and family with two children from the donor eggs is highlighted. The donor knows these children, and the children are aware of how they were conceived. Kids are made — giving a new meaning to where babies come from:

It’s the sort of relationship that many children born from the technology will never experience. That’s especially true as the industry ships more frozen eggs across borders, many sourced from nations without strong right-to-know laws or reliable record keeping. Karen has donated 336 eggs, in 7 retrievals over 5 years in 3 countries. At least five pregnancies have resulted. Rupert and Matilda are the only children born of her eggs she knows.

Member discussion