Three good ideas from science writer Ed Yong

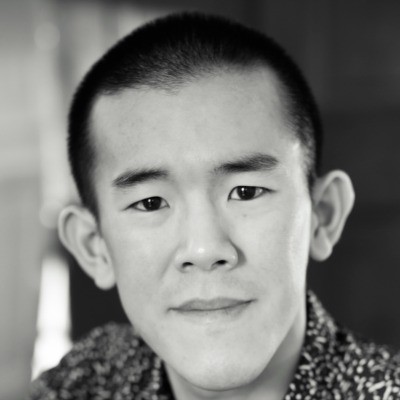

In the podcast "The Interview," David Marchese chats with science writer Ed Yong about burnout, science journalism, and Yong's newer hobby, birding.

Yong is among my favorite writers and thinkers. His Atlantic and Pulitzer winning writing made me understand the pandemic, and science with politics.

His book Immense World is one of my favorites. It's about animal senses, and the humbling fact that we humans are naked calculators stumbling on the harsh earth. We have nothing on animals. Animals have super abilities from electrocution, heat detecting tongues, echo location, mighty appendages. Plus, I learned about the loopy word umwelt: how organisms use senses to create their reality.

https://www.penguinrandomhouse.com/books/616914/an-immense-world-by-ed-yong/

Three items stood out from the conversation. First, science and nature, broadly speaking, can do more than explain the world. Science and nature can pull you back into the world. As Yong says:

"We exist at a time when we are being crunched ever inward. Whether it’s through a novel virus, or frayed social connections, or algorithms that feed us more of what we already were seeking out. There is a kind of implosive effect of the modern world, and the science and nature writing that I’m prioritizing, and the birding that I do, are all counters to that. They are a way of radiating your attention outward."

Crunching inward feels right. We are laser locked on our phones like we get paid to check everything every hour. Everyone I know is like in a time famine, it seems. People don't have time to pause; rather they are hunched in the constant present with a new hot gas ball of stuff that hits our screens every day. Refreshed, refreshed.

Plus, our infrastructure severs friendships and IRL time. We are fettered to improve our selves, to be Well and optimized. To be perfect in every way that we hardly take time to do imperfect stuff: learn instruments, play sports, sit on a porch and have a gaff. Have a drink. Go for a walk. Volunteer for an organization we believe in. Walk in the forest, look for some birds.

Non-optimized time is where we make connections. Friction is good. Instead, we are in a time famine because we need to be always doing something productive. This is how it feels to me, much of the time, at least. I have struggled with this feeling for years — wanting to optimize every moment and help it make me more productive. This can keep someone from being happy, or scared to be happy.

A fancy way of putting it: we can become solipsistic. The spine shattering idea that our mind is the only one that exists, and reality doesn't exist outside our minds. nothing is outside. This makes it hard to connect with other people.

Yong's idea for going into nature as an escape offers a way of moving that attention outward. Turn the lighthouse out to sea rather than down the hallways of the self. I'd extend this even beyond nature, which is good, but also music, art, movies, knitting, history. Get obsessed about something other than yourself: go to social events, text specific people about something. Looking outward can be antidote.

We are driven to think we are on our own, and we should do everything on our own. This idea is sometimes advertised as an entrepreneurial mindset. The notion that every American should become their own LLC, which extends out to saying that much of the labor force should be a company of one because you can be more successful than you ever would with a group, or creating solidarity among fellow laborers.

Work becomes transactional, life becomes branded and all about You. Every action, post, should feed this. Doing everything on your own is more often myth than reality — and to strive that, to perpetuate it, means to give away power, and, to me, an obsession for self and work that feeds that feeds that self. When everything serves the self, we lean to the individualistic, competition with others, and the personality becomes a tool for money. I am not sure this is a place I want to go, but I've been charmed by the idea of it: doing everything on my own.

All this is to say, Yong offers science as a method out of your head, out of the recursive hunger to build an company of self. The intentional act of learning about the world around you offers a healthy escape. But not just ignoring the problems, but getting to know the world in a new way, and perhaps, taking on problems better than you ever would alone.

Secondly, Yong offers his thoughts on journalism and the shopworn idea of objectivity. "Objectivity is one of the most oversold concepts in journalism. It allows people to pretend they don't have biases, when they absolutely do." Journalists and writers should strive to be chairs rather than cameras, I beleive. Capturing events, a persons's challenge from an objective point of view is not possible, really. Every choice has a bias from what you decide to cover, to what headline. Each choice has a subjective process around it.

Instead, Yong says writers should aim to use fairness, honesty, accuracy, and compassion. Journalism can be a caretaking profession.

To state another journalism phrase: Discomfit the comfortable, comfort the uncomfortable. But leave the old idea of objectivity at the door: the view from nowhere is impossible. Every decision a journalist, writer, or editor makes comes from somewhere. In fact, objectivity, saying your creation is free of bias, can even be harmful.

Lastly, I like what Yong offers about hope. He evokes the idea from Mariame Kaba who has said "Hope is discipline" and activist Paul Farmer's fighing the "long defeat":

There are three ideas that come to mind. One is a quote from the amazing Mariame Kaba, who says, “Hope is a discipline.” She argues that hope is not this nebulous, airy thing. It is a practice that you cultivate through active effort. I think of a line by the great and late global-health advocate Paul Farmer, who said that he “fought the long defeat.” By which he meant that he was often swimming against forces that were extremely powerful, and he knew that he was going to suffer defeats and setbacks, and that he was going to fight nonetheless.

From NYT, or where ever you pack your podcasts:

P.S.

- Attend and support a Stand Up for Science event happening on March 7th. I'm going to the Denver one!

- A big resist list for getting a handle on what's going on with the current administration and ideas for action.

(H/T to Liz Neeley for those two links, check our her newsletter, which offers a great mapping for what's happening to the sciences because of the political action of the Trump adminstration, and what you might be able to do about it.

- See Ed's talk at XOXO, equally great:

See Ed's Newsletter to catch his monthly updates (and extraordinary bird pics), including his latest that offers a starter guide to birding, which I copied below:

How to Get Into Birding

One of the questions that David asked me, which I believe isn’t in the final cut, was: What advice do you have for people who want to get into birding? I’m pretty sure I garbled the answer so here’s a more considered response. I have four suggestions, which I’ll offer from least important to most.

4) Learn about your area. eBird is a great resource for finding good birding sites close to you, which are often unlikely areas. Talking to birders—the randos you see out and about with cameras and binoculars around their shoulders—can be a goldmine of tips. For me, part of the joy of birding is getting to know the land in a deep and local way. But also: If you’re disabled and housebound, you may be restricted to whatever you can see or hear from your yard or window, and that’s totally fine.

3) Use the Merlin app. Merlin is best known for identifying birds from their calls and songs. It isn’t perfect but it gets more things right than wrong and it’s exceptional for beginners. Birding is an auditory experience as much as it is a visual one and Merlin is invaluable for training your ears. (Moreover, the app secretly doubles as an encyclopedia. You can plug in your location and date, and it will rank the potential birds by your odds of encountering them.) But also: If you’re deaf, birding isn’t an auditory experience, and that’s totally fine.

2) Get good binoculars. Birding can be expensive if you shell out on high-end cameras, spotting scopes, and travel; it can also be extremely cheap because none of those are essential. The one financial outlay that is hard to escape is a good pair of binoculars. I use the Nikon Monarch M5 8x42, which are $280. I use them almost every day and they’re basically indestructible. Cheaper models exist, but past a certain price, your value-for-money nosedives. Rinky-dink bins are only marginally better than no bins at all, while the good models are transformative. But also: If you can’t afford binoculars, you’ll just have to bird without them, and that’s totally fine.

1) Make a choice. For me, this is the only non-negotiable part of birding—an activity that is 90% intentionality and 10% everything else. You have to choose. Decide that birds, and the natural world more generally, are worthy of your time and attention. Decide that you care enough to try and look at them or for them, with your eyes or your ears, from your window or in a national park. Tell yourself that identifying birds might seem challenging but is not impossible, and that learning subtle differences is not an exercise in nerdy trivia, but a profound act of respect towards our non-human peers. Realize that spending time with birds is not a means of escapism that you should feel guilty or self-conscious about, but an immersion in the full extent of the world. Choose. That’s it.

- The Texas writer, Lawrence Wright's long exploration into the world of Texan women on death row, and the nuns who helped them. Fascinating read.

Member discussion