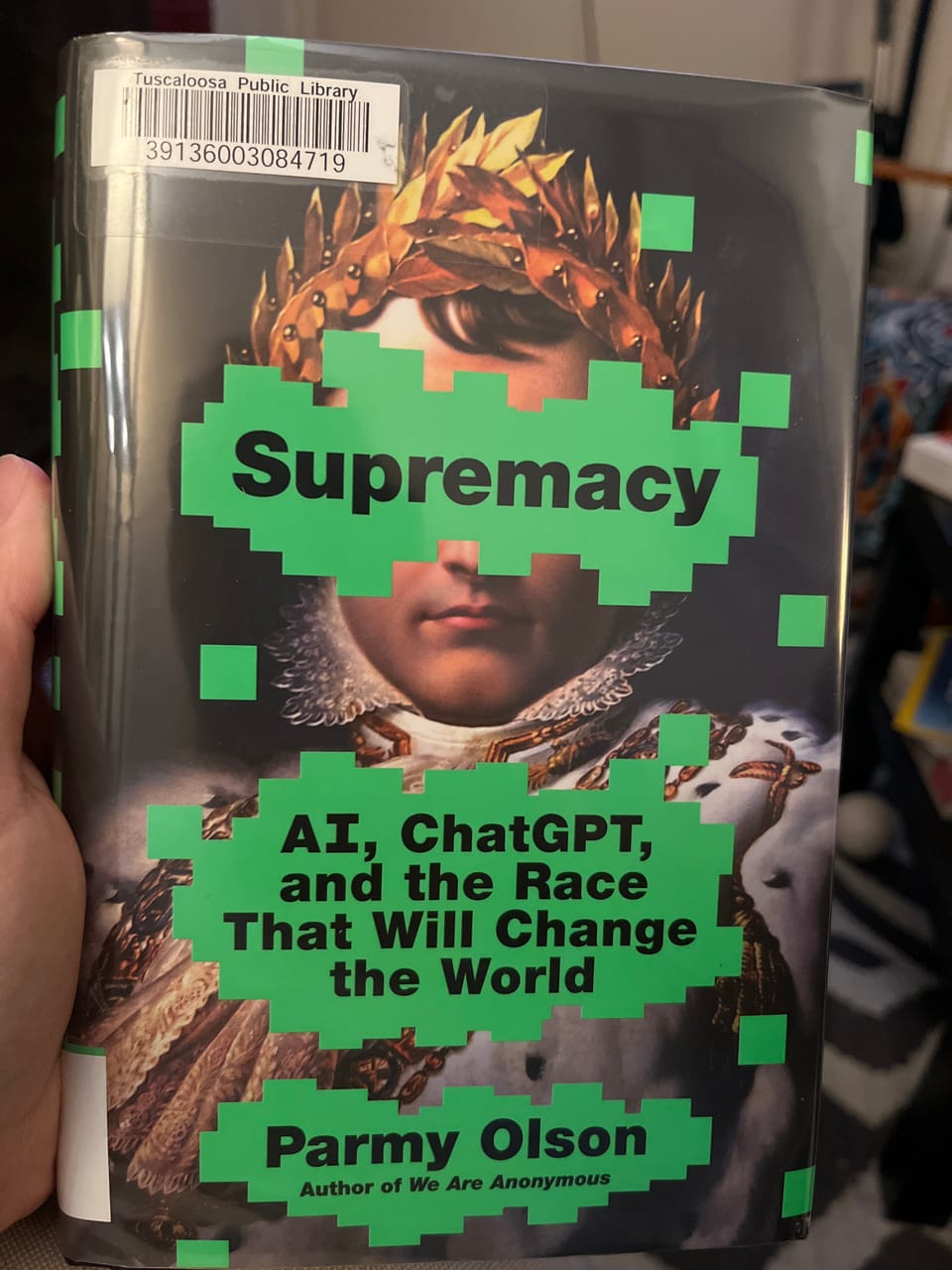

Book: Who is the AI Race for?

Parmy Olson's excellent book Supremacy: AI, ChatGPT, and the Race that will change the world delivers clarity and synthesis. If you need a handle on AI, who built it and why, and how the tech is everywhere in conversation and software, this is the book to pickup.

https://us.macmillan.com/books/9781250361622/supremacy/

Parmy outlines two of the most significant people behind the rise of AI in OpenAI's Sam Altman and DeepMind's Demis Hassabis. With so many damn articles written about these men — as with all the leaders in tech — this book offers an all-in-one place to ride through their lives, and a sidecar look at rise of AI within Big Tech's ecosystem.

The language and breeziness of the book creates a wide-open doorway of accessibility for learning about AI and how the technology works. My brain felt the extra context of where Sam Altman went to high school, and how that shaped him. I understand Demis's first jobs working on video games and how that releates to his desire to make a God-like intelligence machine. It's like hearing the tale of AI over a cup of coffee from someone who was there, across the last 40 years.

You'll hear everything explained from Microsoft's failed (and racist) chatbot Tay to how the vital computer architecture, the transformer was built and changed what was possible with deep learning in computers. ( This is explained in the landmark 2017 research paper "Attention is all you need," which helped kickstart OpenAI's creation ChatGPT.)

There are also solid reminders like AI is a marketing term born out of a workshop at Dartmouth College in 1956. It was an idea built on "thinking machines." The term of artificial intelligence stuck because it best anthropomorphized computers while over exaggerating what these computer could do — something we still do with chatbots, no matter how human-like they might sound.

(Side note: The sci-fi novels of Dune (and film adaptions) use the term Thinking Machines in the fictional histories of the world, which are defined as a set of robots that humans went to war with. The result: "Thou shalt not make a machine in the likeness of a human mind." Perhaps, modern tech builders should listen to cautions from the Dune universe?!)

The term AI simplifies the tech, and makes it easier to bring people to the table, and use the tech, talk about it. For investors, it makes it easier to fork over lots of dollars. It makes the tech marketable, slick, smart, powerful, etc.

Although, chatbots sound real enough. See Google's new marketing behind their AI model Gemini Live (this is to convince you it's like a human assistant).

Or there's the millions of people using the services of Character.AI, which is now being sued because of a chatbot causing a teen's suicide.

All risks of thinking machines aside, the tech has much of the human-thinking population charmed. The spellbound say things like: I've have never seen anything like this. This is the worst it will ever be. The tech is transformative. It will change how we work. Etc, etc.

I've been one of those people. I constantly wonder how this technology could do my jobs differently, or better. But, for me, it doesn't quite stick. I can't seem keep it in my routine, or fully trust it for research, especially. I keep trying, but am deeply unsure. I like doing it myself. I like the work of learning and writing it out myself — for reasons I can't explain, yet.

For others, AI is an economic opportunity, for both creators and consumers. The cofounder of Character.AI, and a key researcher on making the transformer, Noam Shazeer puts his belief in the tech this way: "...search was about making information universally accessible, AI is about making intelligence universally accessible and making everyone massively more productive."

Shazeer believes AI is a "quadrillion" dollar technology — wealth is ready to crank out. But there will be costs; a teens death is just a taste of that cost, AI slop is another, sexual abuse victims is another. Even if costs don't scare builders away, hubris and promise can come back to haunt. Olson brings out the example of researcher Henry Markram who wanted to mimic human intelligence on super computers (via TED talk) with the Human Brain project, but 10 years in, those dreams fell short, and one critic called Markram a man with two-personalities: "“One is a fantastic, sober scientist … the other is a PR-minded messiah.”

For the Shazeers and Atlmans and Hassabiss of the world, the potential of this tech is powerful, the promises are earth shattering in potential. "Solve intelligence, and you solve everything else," was on DeepMind's early pitch decks. Hassabis wanted to create Artificial General Intelligence to understand where humans come from, and just like the main character in a coming-of-age film, figure out our purpose.

(Alien franchises Prometheus's anyone? A corporate tycoon searches space for a powerful being to ask similar questions.)

In other words, Hassabis wants to create a form of God. Some studies suggest if when thinking about God, you're more likely to take up AI's ideas. Google, after all, has been like going into a confession box: you type in fears, hopes, mistakes, dreams, and stray thoughts into the search bar. Why not the chatbot prompt that talks back to you?

https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.2218961120

Altman believes a general (and legitiment) artificial intelligence will unlock an abundance of wealth, transforming our whole financial system, recalibrating the capitalistic way of doing things — a framework that has treated him well, I'd just like to add.

But to get there, they need more of everything. "...from money to pay your researchers," Olson writes, "to data to train your models and powerful computers to run them."

Thus, AI hitched to Big Tech — DeepMind to Google (Alphabet), OpenAI to Microsoft. To bring god inside a computer, and create economic abundance that will disrupt our relationship to money, you need more, more money included. To solve intelligence, you need more of everything. Big Tech provides the more.

For example, note that one of the most successful advertising firms of all time is a tech company — Google, which has gotten most of its revenue from advertisements (90% Olson notes, submitting the book in spring 2024). "Google's leadership still cared about getting people to buy stuff they don't need." As Google's website states:

https://about.google/how-our-business-works/

Altman's likely thinking: How you make AGI isn't important, only that you make it. Wealth-abundance and poverty-eliminator dreams of AGI smashes critical thinking, takes on a buzzword in the mind, and blinds with marketing shininess. The promise creates followers.

"In reality, OpenAI was making more wealth for Microsoft than it was for humankind," Olson writes. "The benefits of AI were flowing to the same small group of companies that had been sucking up the world's wealth and innovation for two decades." It's hard to argue with that.

This book clearly shows how those wires connect, and the hissing sparks used to wield the scaffolding together. There aren't solutions here in these pages, but it gives you a lay of the land.

AI might be a great toy, and might help me do my job a bit, and I am all for an invention that could solve economic hardship, vacuum up inequality. But, I ask: prove it. After spending all that money, who will it benefit? How will the people outside of Big Tech benefit? Or is this all a marketing scheme, a nice PR story? Did they invent a savior machine, or an economic engine for the already-wealthy and powerful?

AI's big promise is it will save time: Save me from working, save me from drudgery, which every piece of software has promised, but often adds another complication to my life, or takes away more power, even if it gives a little bit too — I still like technology a lot, but it's the power dynamics I don't like, which I'm only beginning to understand. Olson helps me understand just a bit more.

But maybe AI isn't made to save time, only make us better with the time we have. Take a radiologist for example. Say they do a scan, and then apply the AI, and if the AI finds something they missed or didn't expect, they go back and double check. A radiologist spends the same amount of time checking an X-ray, but now uses AI to help. Hank Green has said on the Hard Fork podcast he does the same for fact-checking his scripts.

If AI helps us do our jobs better, serves as a safety cap on our work, okay, but I am unsure it will take time away — and I'm even more unsure Big Tech will create a entity thinking machine. (Or that we should make a true thinking machine). It's not God doing your job, or giving you important life advice — it's still just (hyped) software.

https://locusmag.com/2023/12/commentary-cory-doctorow-what-kind-of-bubble-is-ai/

If you're like me, you're starting to question AI's true applications and the motivations of the companies behind the Big Tech race of our time.

P.S.

Any tech race makes me think about Center for Humane Technology's Three rules for humane tech:

- RULE 1: When we invent a new technology, we uncover a new class of responsibility. We didn't need the right to be forgotten until computers could remember us forever, and we didn't need the right to privacy in our laws until cameras were mass-produced. As we move into an age where technology could destroy the world so much faster than our responsibilities could catch up, it's no longer okay to say it's someone else's job to define what responsibility means.

- RULE 2: If that new technology confers power, it will start a race. Humane technologists are aware of the arms races their creations could set off before those creations run away from them – and they notice and think about the ways their new work could confer power.

- RULE 3: If we don’t coordinate, the race will end in tragedy. No one company or actor can solve these systemic problems alone. When it comes to AI, developers wrongly believe it would be impossible to sit down with cohorts at different companies to work on hammering out how to move at the pace of getting this right – for all our sakes.

Member discussion